Four Essays, One Dimmer Switch

These four pieces belong together because they’re really one long mood report, arranged from darkest to lightest—not as a redemption arc, but as a gradual widening of the frame. It starts where I’m most worn down, naming the strain plainly, and then moves through the more philosophical problem of what I can reasonably “hope” for in a universe that doesn’t bargain. From there it shifts into the smaller, sturdier practice of gratitude that refuses to turn into a sermon. And, it ends with the most unglamorous miracle I know: a pop song, uninvited, dragging me back into my body for three minutes and reminding me that joy can still show up in the cheap seats.

1. This Can’t Go on, and yet it Does

The first thing I need to say, plainly, is that I am not suicidal. I’m not making a coded announcement. I’m not asking anyone to read between the lines for a hidden plan. I’m still here. I want to be here. I love my family with the kind of love that makes the room feel structurally sound. I’m grateful. I’m tethered.

Still, I’m sad in a way that doesn’t politely stay in its lane.

Lately, I tear up at almost anything that knows how to press on the right nerve. McCarthy does it, obviously. The Sunset Limited hits that familiar bruise of belief and despair and the blunt question of whether any of this is bearable. The Passenger and Stella Maris do it too, in a quieter and stranger register: grief with a physics textbook open, sorrow dressed in math, that lonely feeling of being a mind trapped inside a mind. Then music does it. Dan Raeder’s Smithereens. Bach. Other classical pieces that feel less like songs and more like someone describing the architecture of longing. Then some cheap pop, because sometimes the most embarrassing little chorus is the one that slips past your defenses.

Tears don’t mean I’m falling apart, exactly. They mean the door is swinging on loose hinges. Everything gets in.

The Body That Won’t Let Up

Multiple sclerosis has a way of turning the body into a constant conversation. You don’t get to “focus on your health” like it’s a weekend project. You don’t get to take a day off from inhabiting the thing. Symptoms arrive like emails you can’t unsubscribe from. Treatments and trials promise a lot in the language of progress, then deliver something messier, partial, ambiguous, or flat-out disappointing. The drugs help in some ways and fail in others, and it becomes hard not to feel like you’re living inside a compromise.

There’s a particular kind of fatigue that comes from trying, sincerely, to do all the right things and still not getting relief. It’s not just physical. It’s moral exhaustion. It’s the feeling of being a good citizen of your own life and still watching the system malfunction.

I’ve never harmed myself. I’ve never wanted to. That’s part of why this is so disorienting: the body has done harm on its own, over time, like a slow betrayal carried out in daylight. I can’t pretend it hasn’t cost me things. Vision. energy. spontaneity. the easy confidence of making plans without first checking a hundred invisible variables.

Some days, the hardest part isn’t even pain. It’s the repetition. It’s waking up into the same negotiations again: how much can I do, what will it cost, what will I have left for Christa and the kids, what kind of father am I on a day when my legs and eyes and stamina have already voted no.

Solipsism, Revisited

When I was eighteen, I flirted with something like solipsism. Not in the smug dorm-room way, not as a philosophy flex, but as an actual creeping dread: the possibility that I was alone inside my own head, that everyone else was just a projection, that reality was a locked room and I’d never find the key.

I grew out of that phase, mostly. Life gave me too much texture to keep believing in that kind of emptiness. Love is stubbornly real. Parenting is painfully real. The world refuses to stay theoretical when you’re wiping applesauce off a high chair, or listening to your kid tell you something wise, or watching your partner carry a thousand things without complaint until you finally notice the strain in her shoulders.

Still, illness can bring that old feeling back in a new costume. Not “nothing is real,” but “I’m sealed inside this body and I can’t get out.” It’s isolation without the philosophy vocabulary. It’s the sense that everyone around you is living in the same house, but you’re stuck in one room with a lock you didn’t install.

That’s the moment where art starts to feel less like entertainment and more like a tuning fork. McCarthy, Bach, a sad album, a bright pop song with a cheap hook: they vibrate against the same hidden metal. They find the place where grief is stored.

The Text Message That Landed Wrong

The other day, I texted Christa an essay idea and wrote, “this can’t go on.”

That sentence makes sense inside my head because it’s not a threat. It’s not a plan. It’s not me announcing a farewell tour. It’s me naming the truth that the current level of strain feels unsustainable.

Still, imagine receiving that text from your partner after a decade and a half.

When I picture it from her side, I feel a wave of guilt so immediate it’s almost comedic. Of course it scared her. Of course it would. That’s what love does: it hears danger in anything that resembles a cliff edge.

I wish I had written something truer and less sharp, like “I need a break,” or “I’m not okay lately,” or “I’m safe, but I’m struggling.” Those are the same message, just without the cinematic lighting.

Privilege Doesn’t Cancel Pain

Here’s the part that tangles me up: I’m blessed in real ways. Family I adore. A marriage I trust. Kids who make my life bigger. Material stability. People who show up. Plenty of privileges that many don’t get, and I’m not blind to that.

But, gratitude isn’t anesthesia.

Gratitude can sit right next to sorrow like two people at the same table, eating the same meal, refusing to merge. I can feel lucky and still feel crushed. I can love my life and still want to stop carrying it for a minute. I can be thankful and also angry, because the fact that things are good in many ways doesn’t mean the hard parts don’t count.

Sometimes the guilt is its own extra weight: the shame of suffering “too much” in a life that looks, from the outside, like it should be enough. That shame doesn’t help anyone. It doesn’t make me more humble. It just makes me quieter.

What I Want, Simply

What I want is not to disappear. What I want is not to hurt myself. What I want is a break that actually counts. A pause deep enough that my nervous system believes it.

I probably do need to talk to a professional. That’s the honest line. Not because I’m in immediate danger, but because I’m carrying something that keeps spilling over, and “no time” is a terrible long-term strategy. Time shows up in other places anyway: in tears, in irritability, in the hollow feeling after I pretend I’m fine for one more conversation.

This is me saying it clearly: I’m safe. I’m here. I’m also worn down.

If you’re reading this and you’re worried, you can ask me directly. I can handle the question. I’d rather answer it than have you guess. If I ever do start feeling unsafe, I’ll say so, and I’ll get help immediately. That’s not drama. That’s a promise.

For now, I’m doing something smaller and more realistic. I’m naming what’s true. I’m letting the sadness be seen in daylight, where it looks less like a monster and more like a signal. Then I’m going to take one concrete step toward support, even if it’s inconvenient, even if it’s overdue.

Because this can’t go on.

And, yet it does.

So, I want it to go on differently.

2. Hope, Optimism, and the Words I Keep Not Using

I’ve noticed something in my own writing and thinking, and once I noticed it, I couldn’t un-hear it.

I avoid the word “hope.”

Not completely. I’m not allergic. I’m not doing a purity test. But when I’m talking about my health, the future, the world, or the slow and ordinary brutality of time, I reach for other words first. “Optimism” shows up. “Orientation.” “Commitment.” Sometimes, just “I think things can get better.”

People sometimes read that as a mood. As personality. As if I’m either an optimist by nature or a person who’s trying to sound brave.

It’s not that.

It’s mostly a linguistic decision that carries a philosophical weight I can’t quite set down.

Because to me, “hope” has a shadow.

Hope is usually offered as a virtue. A candle. A life raft. But in my ear it often arrives paired with its twin, whether we name the twin or not. Hope and fear. The same coin, two faces. One says please let it be okay. The other says please don’t let it be awful. They differ in posture, not in structure. They both feel like a kind of leaning—an emotional forward tilt toward a future you can’t control.

I don’t want to live in that lean.

Not because I’m above it. Not because I’ve transcended anything. But because, the more I think about how the world works—deterministically, or even with some randomness mixed in—the more “hope” feels like I’m trying to negotiate with the universe. Like I’m filing a request. Like I’m speaking to a cosmic manager who might approve or deny.

That kind of language makes sense in certain metaphysical climates. If you believe someone is listening. If you believe outcomes are flexible in a way that responds to pleading. If you believe the future is a door that swings based on how well you want it.

But, I don’t believe that.

I talk a lot like a determinist because it gives me clean edges to write against. If there’s genuine randomness under the hood—quantum dice, chaotic noise, whatever—fine. The point still stands. Whether the future is fixed or just partly stochastic, it isn’t something I can charm into kindness by calling it “hope.” The universe doesn’t blush. It doesn’t bargain. It doesn’t reward the right tone of voice.

So, the word starts to feel… off. Not morally off. Just structurally inaccurate.

Optimism, on the other hand, feels like a different kind of statement. It doesn’t feel like pleading. It feels like an assessment.

Optimism says: given what I know, I expect better outcomes are possible, and I’m going to behave accordingly.

That’s not a prayer. That’s a posture with elbows.

It’s also less theatrical. “Hope” can carry a kind of soft-focus glow. Even when I mean something plain—“I think the new drug might help,” or “I think my kids will be okay”—“hope” can sound like I’m doing emotional incense. Like I’m trying to summon a vibe.

I’m not trying to summon a vibe. I’m trying to name what I’m actually doing.

Which is usually this: gathering evidence, noticing patterns, accepting what I can’t control, and then choosing a direction anyway.

That choice matters, even if the universe is deterministic. In a deterministic world, I’m still part of the chain. My attention is part of the chain. My habits are part of the chain. My decision to show up for my family—especially on the days when I’d rather disappear into headphones and darkness—is part of the chain. My optimism isn’t a magical force that changes fate. It’s one of the forces fate includes.

This is where the word choice bleeds into ethics, whether I want it to or not.

Because if hope is often a cousin of fear, optimism is often a cousin of care.

Hope can be passive, even when it’s sincere. It can be a waiting room. Optimism, the way I’m using it, isn’t waiting. It’s closer to commitment. It’s a way of saying: I’m going to keep acting as if reducing suffering matters, even if the universe doesn’t hand out gold stars for trying.

That’s the other “contradiction” people sometimes hear. I write about radical uncertainty—about not knowing what consciousness is, or what the universe ultimately is, or whether the human story has any metaphysical backing. And then I write like a moral realist anyway, like some things are wrong in a way that doesn’t evaporate when you change the lighting.

The language choice is part of how I hold both.

If I don’t know the deep story, I can still know enough to recognize suffering. I can still know enough to see that some configurations of life are kinder than others. I can still know enough to want fewer children terrified in their own bodies and more children safe in their own homes.

That’s not a grand theory. It’s a stubborn preference so consistent it starts to feel like a fact.

So, when someone asks me if I’m hopeful—about my body, about medicine, about the world—I understand what they mean. They’re asking if I’ve given up.

But, I’d rather answer with a different word, because I’m trying to describe a different thing.

I’m not waiting for a benevolent universe to notice me.

I’m choosing an orientation. I’m choosing a stance. I’m choosing, as much as anyone ever chooses anything, to keep leaning toward care instead of collapse.

Call it optimism if you need a label. Call it refusal. Call it realism with its sleeves rolled up.

Just don’t make me say “hope” unless you want me to also talk about fear—and I’m trying, most days, not to give that coin more airtime than it deserves.

3. Gratitude, Without the Sermon

There’s a version of me you could assemble from my writing, a paper person made of sentences and small scenes.

He talks about my kids, Christa, the way a morning can be stitched together by something as ordinary as coffee and the right kind of quiet. He notes how tools—AI, accessibility tech, whatever helps—can tilt the day a few degrees toward doable. He returns, again and again, to gratitude, like it’s a familiar porch light.

If you only met that version, you might think I live in a steady glow. Like I wake up grateful the way some people wake up hungry.

That’s not the life behind the paper.

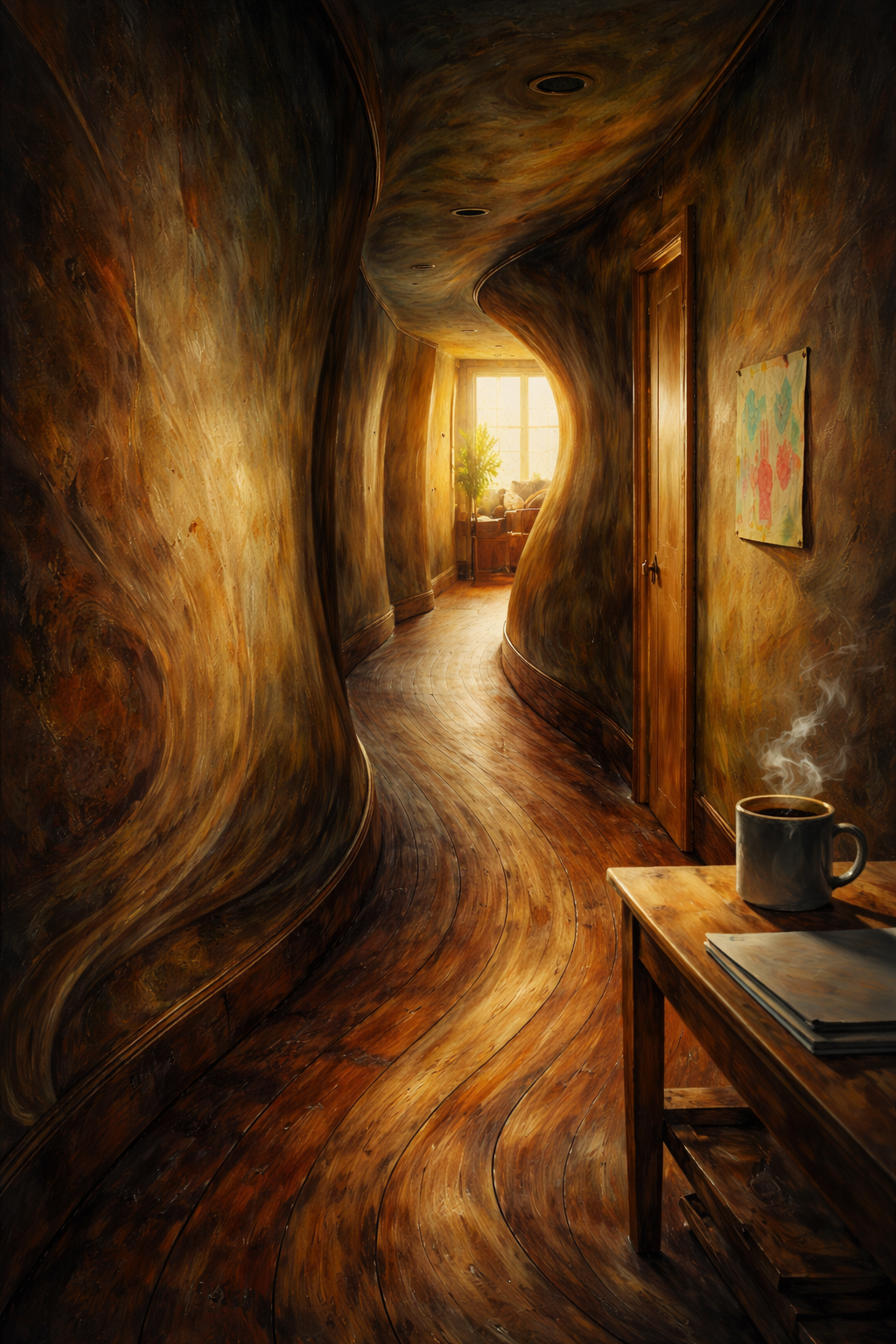

I’ve touched the nadirs of despair. Not the cinematic kind with a clean monologue and a swelling score, but the slow kind—days that drag, hope that frays, the sense that your own body is an argument you didn’t want to have. There have been mornings when the future looked like a narrowing hallway, and I couldn’t find any angle from which it felt generous.

In those places, gratitude isn’t a warm practice. It’s a rumor. A distant thing other people talk about, like a city you used to live in.

I also know the branded version of gratitude—the greeting-card voice, the tidy “practice,” the soft-focus promise that three bullet points a day can turn pain into wisdom. That version makes me wary. It can flatten suffering into a lesson and treat every wound like an opportunity for better posture. Sometimes it feels less like comfort and more like an eviction notice: please leave your grief at the door.

So, when I talk about gratitude, I’m not trying to preach it. I’m not trying to sell it. I’m not pretending I’m cured of bitterness or fear or the occasional sharp, stupid rage at circumstances. I’m trying to name something more modest and more honest: gratitude as a direction, not a destination.

Some mornings everything is heavy—the legs, the eyes, the mind. The simple tasks line up like they’ve been given weight vests. On those days, the sentence I’m so grateful to be alive can feel like a lie I’d be embarrassed to say out loud.

But, sometimes I can say a smaller true thing.

Sometimes I can notice my daughter’s hand on my arm, steadying herself on my wheelchair like it’s the most normal thing in the world. Sometimes I can hear Christa humming in the kitchen, a thread of music that doesn’t solve anything and still changes the room. Sometimes a laugh from a podcast hits my brain in the right way, and, for a moment, the world feels less clenched. Sometimes the mug is warm. Sometimes the light through the window is doing that strange, simple work of insisting on beauty.

None of that cancels the hard parts. It doesn’t turn grief into virtue. It doesn’t make the future less uncertain. It just widens the frame. It reminds me that my attention doesn’t have to stay pinned to the bruise.

The trouble is when gratitude gets treated like a moral exam. If you’re not grateful all the time, you’ve failed. If you’re angry, exhausted, or hollowed out, you’re “negative,” as if negativity is a personality flaw and not sometimes a completely reasonable response to life. That’s where gratitude becomes performance, and performance is where honesty goes to die.

I don’t think gratitude is proof of being a good person. I think it’s proof you’re still looking. Still capable of being moved by something small. Still willing to let the world touch you, even when it has also hurt you.

Because I’m human. I still get bitter. I still compare. I still spiral. There is no clean arc where despair is the before and gratitude is the after. It’s closer to a dimmer switch—brightening, fading, brightening again.

Most days, gratitude is not a permanent state for me. It’s a flicker. A brief softening around one bright, ordinary fact: this kid, this mug, this joke, this breath. Not salvation. Just presence.

Maybe that’s why I keep writing about it. Not because I’ve mastered gratitude, but because I haven’t—because I keep losing it, and then, every so often, I find it again.

4. Karma Chameleon, Ears, and the Mood Swing I Didn’t Order

I want to say something upfront, partly because it’s true, and partly because I don’t want to be That Guy.

I am not self-diagnosing. Especially not with something as big and consequential as bipolar disorder. I know people who live with it. I’ve seen how serious it is. I wouldn’t presume to map my messy little emotional experience onto someone else’s neurological reality and then stroll away like I’ve solved the human condition in a paragraph.

Still, I need to name what’s happening in my own head.

Because it’s a lot.

Some days I’m down in it. Despair-adjacent. Drafting essays where I keep insisting—like a legal disclaimer in the fine print—that I’m not suicidal. Which I’m not. I’m not in danger. I’m not secretly writing a farewell note and trying to smuggle it past the people who love me. I’m writing because the sadness is real, and because honesty is kind of the only thing I know how to do with it. Also because my brain, apparently, believes that if I just explain myself with enough precision, reality will stop being reality. (It has not worked so far, but I respect the hustle.)

And, then other days, with no committee meeting or warning label, I swing the other direction. Not into mania, not into a diagnosis, but into this almost embarrassing brightness. Like the world just got turned up a few notches. Like my body is still a problem, yes, but somehow the day is not. Like I can feel gratitude in my chest in a way that’s so intense it borders on ridiculous—like I’m one inspirational quote away from being kidnapped by a wellness podcast.

The stupid part is how small the triggers can be.

The other night, it was a song.

“Karma Chameleon” came on Spotify—completely uninvited, like it had kicked down the door—and I started bobbing my head without asking permission from my own cynicism. I even did that thing where you whisper-sing because you can’t quite sing the way you used to, but you refuse to let that be the end of the story. Not loudly. Not well. But earnestly. Like you’re trying to meet the song halfway, even if your body’s been rerouting roads without consulting you. (My body is basically a city planner who hates me.)

Here’s the thing I realized in real time, mid-bob, mid-whisper, mid-private concert for one.

I am so damn happy to have these ears.

I don’t mean in some vague “count your blessings” poster kind of way. I mean it in the blunt, physical sense. I mean I’m happy that sound still gets in. That music still arrives. That my brain still receives rhythm and melody and whatever strange chemical comfort a bassline can deliver.

My vision is terrible. That’s not a mood, that’s a fact. My speech is worse than it was a year ago. Also a fact. I’ve got the MS roulette wheel spinning in the background like it’s bored and wants attention. There are a dozen little losses, some loud, some quiet, and none of them feel like metaphors. They feel like logistics. They feel like constantly renegotiating terms with a body that keeps sliding new clauses into the contract after I’ve already signed it.

But, my hearing?

My hearing feels like a gift that keeps refusing to disappear.

And, I don’t want to romanticize that. I don’t want to turn this into a “silver lining” sermon where the point is that everything is secretly fine if you just look hard enough. I can’t even “look,” so let’s not do that. Some things are not fine. Some things are grief, full stop. Some mornings I wake up and my first thought is some version of: really? We’re still doing this? We’re still doing this again? Fantastic. One star. Would not recommend.

But, then a song hits, and I remember that my life isn’t only a list of deficits. It’s also a sensory reality, still. Still textured. Still capable of punching through the fog.

Karma Chameleon is a banger. I will not be taking questions at this time.

It’s impossible to hear that song and not feel the engineering of it. It’s bright without being cheap, catchy without being hollow. It’s silly in the way that only confident art can be silly. And when it lands on the right night, it doesn’t just entertain—it rearranges you. For three minutes you’re not a patient, not a case study, not a person with a calendar full of medical appointments and quiet dread. You’re just a human being with a head that can bob. A man sitting by his wife whom doesn’t know what I just said, whisper-singing like a haunted karaoke machine, but still—a human being.

That might sound small. It is small.

But, small is not the same as meaningless.

One of the weirdest parts of this illness—of any long, slow, chronic unraveling—is how it distorts scale. Huge things happen in increments. Your world shrinks by degrees. You lose a little function here, a little ease there, until one day you look around and realize you’ve been living in a different body for months. Years. The losses don’t always arrive like thunder. They arrive like paperwork. They arrive like “press 1 for representative” and then nobody answers.

So, the wins don’t always arrive like thunder either.

Sometimes they arrive as Boy George.

Sometimes they arrive as an old album you forgot you loved.

Sometimes they arrive as the simple fact that the world can still reach you through sound, and it reaches you in a way that feels intimate. Like it’s saying, I’m still here. You’re still here. We can still do this part.

I don’t know what to do with these swings, exactly. I don’t know how to smooth them out or make them more predictable. I’m not sure that’s even the goal. Maybe the goal is just to stop being surprised that a human mind, under strain, can still spark with joy.

Maybe the goal is to let both truths exist at once.

I can be sad, deeply, and not be in danger.

I can be grateful, wildly, and not be naive.

I can draft the heavy essays and still whisper-sing the chorus when the universe hands me a pop song like a life raft.

And, if “Karma Chameleon” can drag me back into my own body for a few minutes—if it can make me smile in spite of everything—then fine. Let it.

Let the song be just plain killer.

Let the ears be a miracle.

Let me bob my head like it matters.