Curtains, Questions, and the Truth

The Sign I Almost Got Right

This story starts before the vacation even begins, in the bright, stressed theater of airport security. We were flying down to Delray Beach, Florida, for a short trip. The line was noisy and tight and full of angles: plastic bins, moving belts, sharp voices, the kind of environment where my vision doesn’t just struggle, it retreats.

I knew I needed help. The problem, as always, was the little gap between needing something and saying so.

I caught the attention of a TSA agent and tried to sign “blind.” I’d remembered it wrong. I thought you slowly swipe your hand down over your eyes, like you’re drawing a curtain. That’s what I did—half confidence, half improvisation. I was slightly off, apparently.

But the thing is: he got it anyway.

A pause, a look, a nod. Not pity. Not suspicion. Just recognition. Okay. I understand. Right this way.

And, suddenly, the whole process softened. I moved through the maze with less friction. I didn’t have to pretend I was tracking what I couldn’t track. I didn’t have to guess. The world, for a moment, met me where I actually was.

I keep thinking about that. How often the hardest part isn’t the disability itself, but the social choreography around it—the way you try to stay smooth and unremarkable, the way you want to be “easy,” the way you’re trained, your whole life, to avoid making anyone else uncomfortable.

The Questions That Came After

Then we got to Delray. Vacation. Family. Warm air. The illusion that you can set your body down somewhere like a heavy backpack and forget you’re carrying it.

And, that’s where the real moment happened.

My niece is eight. Eight is such a clean age for truth. Old enough to notice everything, young enough to ask without varnish. On the trip she wanted to talk—not just the quick kid questions, but the second layer. The honest curiosity that follows once they sense you won’t dodge.

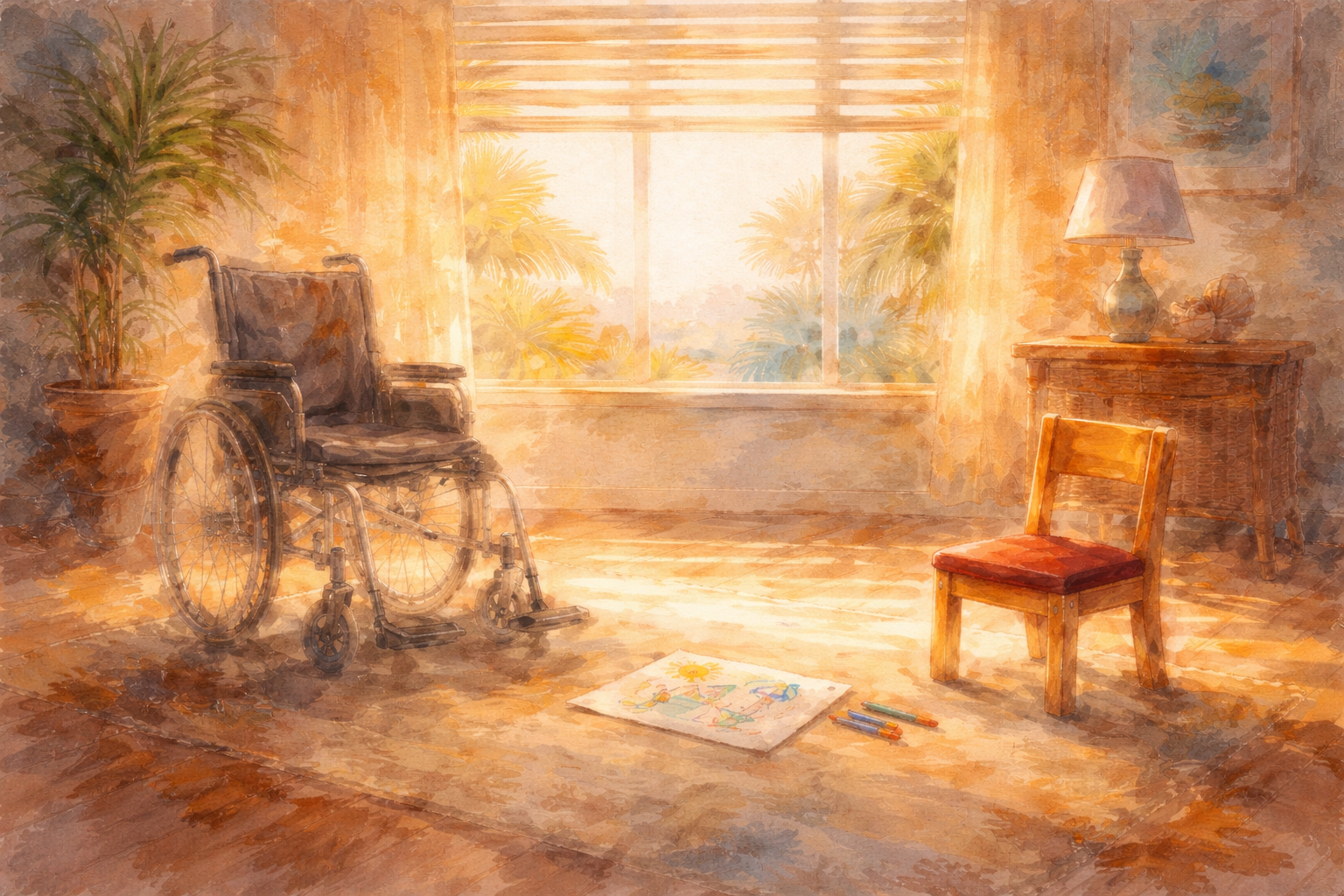

She asked about the wheelchair. Why I’m in it. If it’s hard.

And, I felt that familiar fork in the road.

One path is the performance path—smile, soften, deflect. Make it small. Make it digestible. Keep the air light. Protect everyone from the gravity of it.

The other path is the truth path. Not the deep-end, existential, no-holds-barred truth. Just the simple kind. The kind an eight-year-old can hold without dropping.

So, I told her.

I explained, in plain language, that my body doesn’t cooperate the way I want it to. That walking is unreliable. That some days are harder than others. That I manage anyway. Not heroically—just practically, the way you manage a stubborn door: you learn its quirks, you stop rushing it, you put your shoulder where it wants your shoulder, and you go through at your own pace.

She asked about my slow speech too, that slight lag I can hear in myself sometimes. I told her that my brain is still me, but my mouth doesn’t always keep up. That the words arrive, but they take the scenic route out.

We didn’t plumb the depths. I didn’t turn it into a lecture. I didn’t hand her a brochure. I just stayed with her questions the way you stay with someone at the edge of cold water—steady, not pushing, not pulling away.

And, when we were done, she said something like, “I really like talking to you.”

That line hit me right in the ribs.

Because the fear underneath all of this—the fear under the wheelchair, under the blindness, under the slow speech—is not pain. It’s not even loss.

It’s distance.

It’s the dread that people will back away when you name what’s real. That honesty will cost you warmth. That your body will become a wall between you and the room.

But, my niece didn’t back away. She leaned in. She came closer with her questions, and then she offered me that small, bright sentence as proof that the truth hadn’t broken anything.

If anything, it built something.

Naming What’s True

I’ve been thinking about kids lately, about that instinct to “fake it” when they want you to look at something. A drawing. A toy. A screen held up like a gift. They say, Look! and you have a split second to decide whether you’ll pretend you saw it, or whether you’ll tell them you can’t—not really—but you still want to know.

I used to think telling the truth would be a burden. That it would make them sad, or confused, or uncomfortable. That it would turn a simple moment into a Thing.

But, maybe the Thing is the pretending. Maybe kids can handle clarity better than adults can. Maybe they don’t need a perfectly able uncle. Maybe they just need an uncle who’s actually there.

On the way down to Florida, I signed “blind” wrong and still got understood.

On vacation, I answered my niece’s questions without flinching and got something even rarer: connection without performance.