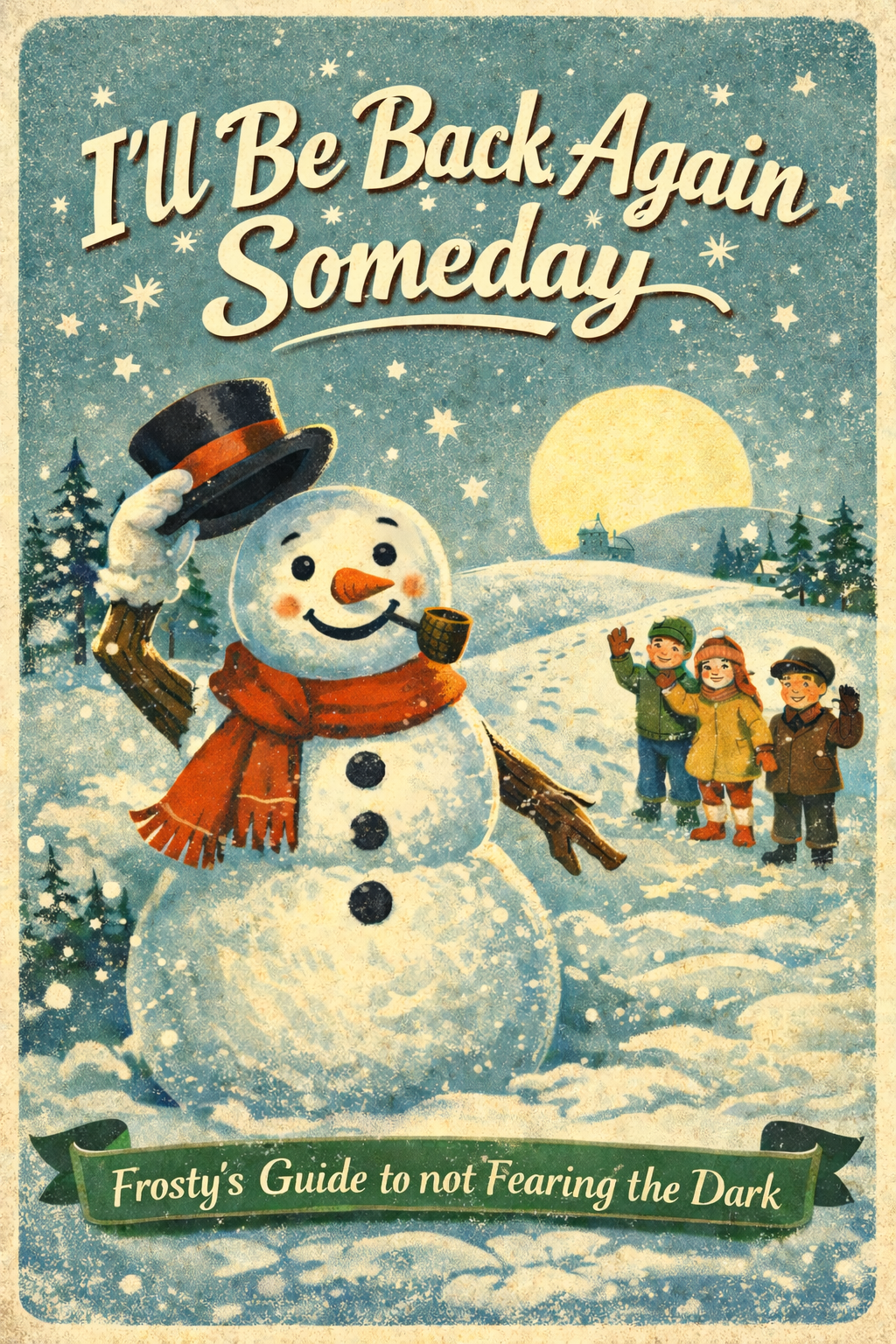

The Melting Point of Existential Dread

I don’t usually turn to a talking snowman for comfort about the end of consciousness, but here we are—running existential diagnostics with a corncob pipe and a silk hat.

At the end of Frosty the Snowman, everything is technically a disaster in the way only children’s media can make adorable. The sun is out. The snow is melting. The kids are crying. Frosty is, from a strict materials-science perspective, becoming a damp suggestion of a snowman.

And, then Frosty, who should be in a frantic meeting with the laws of thermodynamics, leans in and says, “Don’t you cry, I’ll be back again someday.”

That line is doing a lot of work for a character made of weather.

The Adult Horror Story We Secretly Tell Ourselves

Because if you watch that scene with your “adult realism” settings turned on, you can feel the temptation to say something grimly educational. “Kids, I’m sorry, but Frosty has permanently ceased to exist. There is no more Frosty-experience. Please accept this and eat your feelings in the form of candy canes.”

But, the cartoon refuses the modern secular horror story. Frosty doesn’t act like he’s about to be sentenced to eternal blackness. He doesn’t stare into the camera and whisper, “Soon I will be trapped in the void, conscious but empty, floating in a featureless darkness forever.” He says the opposite. He says—relax. This isn’t the kind of ending you think it is.

And, weirdly, that’s closer to the philosophical point than the dread version.

Because the “eternal blackness” picture that a lot of us carry around is a kind of mental bootleg. We imagine death as a place we go, an environment we inhabit, a room with the lights off where we’ll be stuck forever.

But, look at what that image secretly requires: it needs a someone to be there, noticing the absence, enduring the boredom, suffering the nothing.

In other words, the fear of “eternal blackness” often sneaks in a tiny surviving observer—the ghost of you—who will be forced to experience the lack of experience. It turns death into an experience.

The Dreamless Sleep Demo

But, if death is actually the end of the subject, the end of the point of view, the end of the pattern that makes “you” a you… then there isn’t a leftover watcher. There’s no you to sit in the dark and complain about it. The movie doesn’t cut to a black screen and keep rolling forever. The movie just stops.

You already know this, because your body gives you a free demo every night.

Dreamless sleep is not eight hours of personal blackness. It’s not an extended scene where you remain present in the void, bravely enduring the contentless abyss. It’s bedtime… and then—what feels like instantly—morning. From the inside, you don’t experience the gap. You only infer it later when you check the clock and realize you apparently teleported through time while drooling.

Same with anesthesia. Same with fainting. Same with any genuine blackout. Nobody wakes up and reports, “Ah, yes, I spent several hours experiencing nothingness and I can describe it in detail.” There’s just the last moment you remember and the next moment you’re back.

The gap exists for everyone standing outside you, watching the calendar pages flip. It doesn’t exist as a lived stretch for the subject.

The Snowflake Literalist Objection

So, when people imagine death as “eternal nothingness,” the problem isn’t the word eternal—the problem is nothingness being treated like a thing you can occupy. The dread comes from picturing yourself alive enough to witness your own absence. That’s like Frosty imagining he’s going to be a puddle and still somehow be Frosty in there, bored, wet, and resentful.

Frosty doesn’t do that. Frosty is blissfully non-metaphysical. He treats melting as a transition in the same way you treat taking off a winter coat. Not because it’s literally the same, but because the story is pointing at something else: cycles.

Every winter brings snow. Every snow brings kids. Kids bring creation. Creation plus magic hat brings Frosty.

If you’re a strict snowflake literalist, you can object right away. “This isn’t the same Frosty! Those are different snowflakes! That carrot nose is new! The scarf is a sequel scarf!” And, sure—if Frosty’s identity is the exact physical material, then the Frosty of next year is not the Frosty of this year. Last year’s snow is already halfway to the Gulf of Mexico.

But, if Frosty is what happens when certain conditions line up—snow, children, hat, and the collective willingness to say “yes, this is a person now”—then “Frosty” is less a specific object and more a seasonal event. A recurring pattern. A very cheerful weather-shaped process.

The Hat, the Pattern, and the Point of View.

Right now, “me” is a particular alignment of biology, memory, habit, and mood. This alignment produces a point of view. It produces the unmistakable feeling of being here. Over time, the alignment shifts. Some memories fade. New ones get welded on. You become a slightly different you—quietly, continuously, without ceremony.

But, through all of those changes, subjectively, there’s never a moment where you stand in the middle and experience a blank. You don’t experience “not being you.” You don’t experience your own absence. You only ever have the present moment, the ongoing sense of “here I am,” inheriting whatever thoughts and feelings are available today.

And, before you were born? You didn’t experience the void. You weren’t sitting in pre-existence tapping your foot in the dark waiting for your turn. There was simply no you there to wait.

Which makes it very hard to argue that after death you’ll be stuck in some kind of permanent waiting room of nothing. If you’re gone, you’re gone. No observer. No blackness-as-a-place. Just the end of experience for this particular arrangement.

Meanwhile, the world continues to produce experience.

Someday Isn’t A Sequel, It’s A Season

That’s the other part that the Frosty line accidentally gestures toward. “I’ll be back again someday” isn’t only about one snowman. It’s about the fact that the world keeps doing its thing. Snow falls. Life happens. New minds show up. New points of view ignite.

There’s always someone awake somewhere—some baby blinking at light for the first time, some nurse on a night shift, some insomniac staring at the ceiling, some kid trying to explain why Frosty should have worn sunscreen.

Now, to be clear, that doesn’t mean “you” come back as you. This isn’t a promise that you’ll return in a sequel with the same memories and the same favorite songs and the same oddly specific opinions about fonts. The personal pattern ends. The continuity that matters to your loved ones ends. That’s real. That’s the hard part, and no amount of jolly snowman metaphysics should pretend otherwise.

The particular fear of being trapped in “eternal blackness”—as if you’ll survive just enough to be bored forever—that fear deserves to be laughed out of the room.

Not because death is nothing. Not because endings aren’t tragic. But, because the image is incoherent. It takes the one thing death removes—the subject—and quietly keeps it around so it can be afraid.

Frosty’s Tiny Holiday Upgrade

Frosty doesn’t make that mistake. He doesn’t fantasize a miserable puddle-consciousness watching the sun. He just says, in the breeziest possible way, don’t cry. Someday.

And, maybe the most holiday-friendly version of this whole idea is simply this: you don’t have to dread an experience you can never have. You don’t have to fear “being there” for your own non-being. When your hat finally comes off for the last time, you won’t be hovering in the dark thinking, “Wow, this is really dark.”

You’ll be exactly as aware of it as you were of the year 1400.

In the meantime, you get this season. You get this warmth. You get the small miracle of being awake at all, right now, in a world where cartoons exist and snowmen talk and kids cry for things that melt.

I’ll take my holiday philosophy cold, white, and with a little magic.